One element of the project for my ethnomusicology class involves choosing several relevant images and writing annotations about them. For my first image, I have chosen a well-known photograph that has been used many times to represent the music and culture of the Mississippi Delta in the pre-WWII era. The image depicts a lively couple dancing in a juke joint near Clarkesdale, MS, and it was taken in 1939 by photographer Marion Post Wolcott, one of the photographers tasked by the FSA with depicting rural American life during the Great Depression.

The image brings to mind many of the differences between the blues culture that developed in the South during the period from the 1920s through the 1950s, and that which emerged later as the blues gained a more national following thanks to the Great Migration, the Folk Blues Revival, and the development of rock and roll. Blues has always been a performance art form, but in the early days there was a stronger participatory element. Patrons did not go to a juke joint to sit and watch a musician perform. Instead they went to dance, drink, chase members of the opposite sex, and generally have a good time. They may have been drawn by a particular performer, but it was not so much the performer's music itself that was important, but rather his ability to keep the party going through his interaction with the audience.

In one of the articles I read last spring for my honors project on geographical themes in blues music, Ralph Eastman described how this audience interaction shaped early blues performances. He said that in such performances the song itself was secondary to the performer’s ability to entertain, so the best performers could extend a song indefinitely by adding numerous verses and embellishing the song with instrumental fills and stage tricks. Performers would often interact with audience members and improvise verses to communicate directly with individual members of the audience or extend certain parts of the song to encourage a particularly lively run of dancing.

Eastman, Ralph. "Country Blues Performance and the Oral Tradition." Black Music Research

Journal. Vol. 8.No. 2 (1988): 161-176. Print.

Wolcott, Marion Post. Jitterbugging in Negro juke joint, Saturday evening, outside Clarksdale,

Mississippi. 1939. Photograph. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.. Web. 27 Sep 2013.

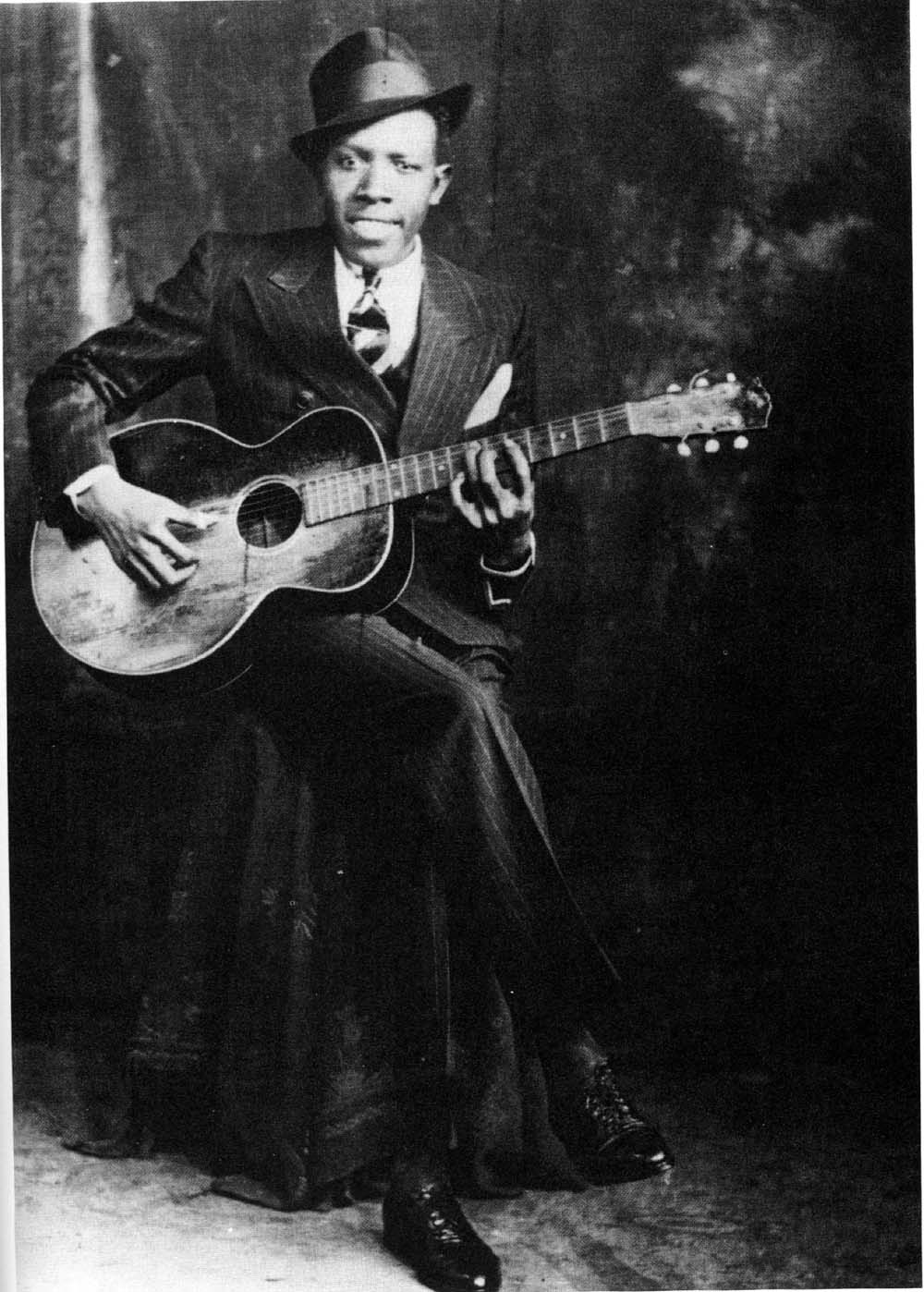

For my second image annotation I am writing about not one image, but two. These are the only two known photographs of legendary Delta bluesman Robert Johnson, and they show two very different aspects of his persona. In the first picture, Johnson is dressed to the nines in a full suit and a hat. In what is obviously a professionally taken photograph, he poses as if he is playing his guitar. The second picture, on the other hand, was taken in a photobooth by Johnson, who sent it to his girlfriend. He is dressed in more regular clothes with no had, and a cigarette dangles from his mouth. The only constant is Johnson's long fingers clutching the neck of his guitar.

The first picture demonstrates an important point about Johnson that Eric W. Rothenbuhler argues in another of the articles I read last spring. Rothenbuhler says that Robert Johnson was the first country bluesman to develop a “for-the-record aesthetic,” carefully crafting each song into a well-structured performance piece, rather than simply employing the traditional model of a repeated guitar pattern and a collection of stock blues verses in not-quite-coherent order. Part of this new performance aesthetic involved cultivating the air of a professional musician, and this is evidenced by the care Johnson put into his appearance in the first photograph.

While first picture, with its dapper version of Johnson, is the more popular depiction, the second photograph shows a side of Johnson that fits better with the legendary stories of a tortured soul who sold his soul to the devil at the crossroads. The simple dress and the lack of a smile suggest more of a rugged loner, while the cigarette and the serious eyes make him look like something of a badass. It is a pity that there are only two photographs of Johnson, but it is fortunate that the two pictures show very different facets of Johnson's personality.

Rothenbuhler,

Eric W. "For-the-Record Aesthetics and Robert Johnson's Blues Style as a

Product of Recorded Culture." Popular Music. 26.1 (2007): 65-81. Web. 3

Apr. 2013.

For my third image annotation, I am going to turn to one of my favorite YouTube videos, which is entitled "Howling Wolf explains what is the Blues." This video is from the DVD Devil Got My Woman: Blues at Newport 1966, which includes performances by several famous blues musicians recorded by ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax behind the scenes at the 1966 Newport Folk Festival. It features Howlin' Wolf performing his song "Meet Me in the Bottom," but it also features a three-minute spoken introduction in which Howlin' Wolf explains what the blues is and then calls out a drunken Son House who is disrupting the performance.

One element of the video that ties in with the readings from our ethnomusicology course is a manufactured sense of authenticity. Some effort has been made to make the room in which the performance is filmed look like the interior of a bar, and the all-black audience is supposed to resemble a typical audience at such a performance. However, the music and the showmanship do not seem to suffer from the manufactured surroundings.

The main attraction of the video is Howlin' Wolf's long rant at the beginning. Howlin' Wolf was a big man with an incredibly gruff voice that was his trademark. Like many blues performers, his on-stage persona is an exaggerated version of various elements of his personality, and the entire speech is delivered while Howlin' Wolf is in this persona. However, he does cover some serious topics. When he says that the blues is "when you ain't got no money," he knows from experience what it is like to grow up in extreme poverty.

The other major player in this video is Son House. Son House came from a very religious background and felt tortured with guilt at making his living playing the "devil's music." However, the temptations of a bluesman's lifestyle proved too much for him. He finally retired from playing music in the 1940s and disappeared, only to be rediscovered in upstate New York in the 1960s. He was able to regain his musical abilities, but alcholism was a constant struggle. Son House had performed earlier, but by the time this video was shot, he had taken full advantage of the bar, and his drunken interjections were beginning to bother Howlin' Wolf.

Howlin' Wolf calls out Son House and uses him as an example of someone who has the blues "because he done drunk up all of his." Howlin' Wolf's comments may be a bit harsh, but what is remarkable is how he weaves together weighty commentary on the human condition--"We talkin' 'bout the life of a human being"--with humorous quips--"Well I was broke when I was born, that's the reason I'm howlin'"--all while maintaining his stage persona. After he finished calling out Son House, Howlin' Wolf returns to introducing his next song, a story about a man who is nearly caught with another man's woman, a frequent subject in blues lyrics.

For my fourth annotation I have chosen a picture of a young Muddy Waters and his friend Son Sims sitting and playing on the porch of Waters's cabin on the Stovall Plantation near Clarkesdale, MS. This was taken during the early 1940s when Alan Lomax of the Library Congress and John W. Work III of Tennessee's all-black Fisk University led an expedition to record the music of the Mississippi Delta. Other musicians had directed Lomax and Work to Muddy Waters when asked where to find the best blues singer around.

At the time, Waters was still in his thirties, and when a small party led by a white man showed up on his doorstep, his shy and reserved manner was nothing like the persona that he would develop in postwar Chicago. Part of this was because African Americans were naturally reserved and cautious around unfamiliar whites in the South, lest they say the wrong thing and get themselves in trouble. This reserved attitude is evident in the terse but polite responses one can hear in the recordings of Lomax's interview with Waters.

The recordings from this early encounter with a future blues great can be found on the album The Complete Plantation Recordings. In addition to the brief snippets of interview, the album features Muddy Waters in a solo setting, singing and accompanying himself on guitar, and also in an ensemble setting, playing guitar with a small string band that included instruments such as fiddle and banjo. Most Delta blues performers had recorded in the former solo setting, but this was largely due to the relatively high cost and complexity involved in recording multiple instruments. It was actually quite common for early blues performers to form small string bands when they performed at parties and get-togethers. However, the solo performances are probably of a bit more interest to typical blues fans because they show Waters performing remarkably well-developed versions of songs that would become his early hits in Chicago, such as "I Be's Troubled," which became "I Can't Be Satisfied," and "Country Blues," which became "I Feel Like Going Home."

The whole episode of the Lomax/Work expedition is informative as a lesson in the history of ethnomusicology. Alan Lomax documented his travels in Mississippi in his book The Land Where the Blues Began, which is a fascinating and enjoyable read. However, he has been criticized for playing fast and loose with the truth, combining his 1941 and 1942 trips into one for simplicity and scarcely mentioning the valuable contributions of Work and his team from Fisk.

My fifth image annotation is drawn from--and my sixth is inspired by--Martin Scorcese Presents The Blues, the only documentary series on the blues that even approaches the scope and ambition of Ken Burns's excellent Jazz. The series includes personal documentaries directed by several famous directors who have been influenced by blues music. The first documentary, titled Feel Like Going Home, is directed by Scorcese himself and written by blues scholar Peter Guralnick and follows the young blues musician Corey Harris on a musical journey he would later record on his album Mississippi to Mali as he travels from the birthplace of the blues in the American South back to the origin of its roots in West Africa.

The above clip shows Corey Harris performing and talking with Ali Farka Toure, one of Africa's most famous musicians, in Mali, a nation with a rich musical tradition with many ties to early African American music. Mali would likely have been the origin of many African slaves taken to America, since most of them came from West Africa. Traditional West African music featured many various stringed instruments, and African Americans attempted to reproduce these sounds in the new world using available instruments, such as the guitar and the banjo, the latter of which was of African derivation. It is remarkable how quickly and smoothly Toure and Harris are able to mesh their styles of music and create a hybrid of blues and African music.

Earlier, in America, Harris and the film crew had visited one of the areas of the United States where African American culture maintained the closest connections to Africa, the Mississippi Hill Country. While the Delta of northwest Mississippi was a hub of blues activity due to the number of itinerant black workers in the rich cotton fields, the Hill Country to the east possessed its own unique culture which was much more condusive to the preservation of tradition. Unlike in the Delta, land in the Hill Country was cheap, which allowed African Americans to own their own land, meaning that families could live on the same land and pass down cultural traditions from generation to generation without interruption.

One of the most unique traditions left in the Hill Country is preserved by the Rising Star Fife and Drum Band. Both the fife and drum were traditional instruments in Africa, but black fife playing almost died out in America. In the Scorcese documentary, Corey Harris visits Othar Turner, who was perhaps the last man keeping the tradition alive. However, before Harris could record with Turner for his CD, the 95-year-old musician died, so Harris instead recorded with Turner's 12-year-old granddaughter, Sharde Thomas, who had learned the fife from Turner. Thomas, now in her twenties, is featured in the above video.

While music enthusiasts and researchers had scoured the Delta for talent, far less attention was paid to the Mississippi Hill Country until the last two or three decades. Alan Lomax had visited the Hill Country in 1959, when he discovered slide guitarist Mississippi Fred McDowell, but the Hill Country just didn't have the strong blues association that the Delta had earned by sending so many of its sons on to successful recording careers. However, in the 1990s, after every stone in the Delta had been turned multiple times, a new generation of blues seekers began to discover the likes of R.L. Burnside, Junior Kimbrough, and Othar Turner and elevate them as the last true, untouched practitioners of country blues. Today, Hill Country blues is a well recognized variant of blues, and its musicians make up a tightnit community held together by families such as the Burnsides, Kimbroughs, and Turners, as well as the Dickinsons, a white family whose members Luther and Cody are members of the popular blues-rock band North Mississippi Allstars and who are backing up Sharde Thomas in the above video.

No comments:

Post a Comment